metamorphoses retold

Ratna Gupta’s creative practice may be seen as physical demonstration/playing out of the complex and sometimes painful negotiations and resolutions of personal, psycho-emotional contradictions. However, her work does not restrict itself to self-referential indulgence. While the ‘self’ has a strong presence in her work, she rejects direct figurative representation for a more actively conceptual/sculptural way of rendering the living figure inscribed by all its contradictions and fragilities. Representations of the body whether in the resin pieces or the black and white photographs are as fragmented as the mind is schismed, in search of completion and balance.

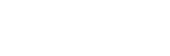

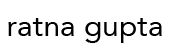

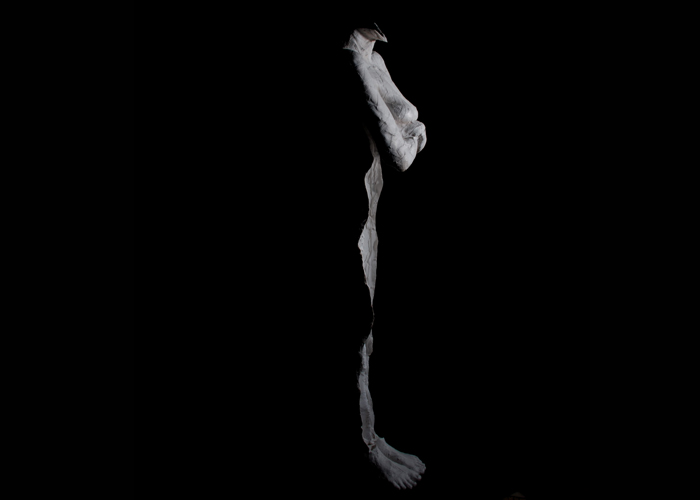

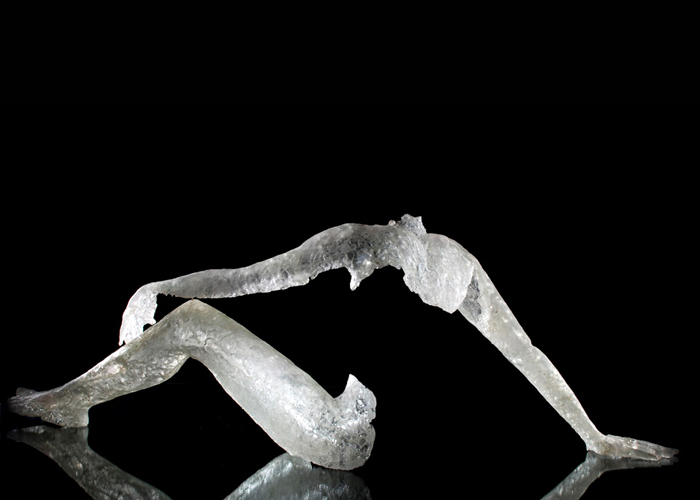

The show, Metamorphoses Retold, is predominated by an installation in resin comprising eighteen pieces of sculptures, to form, Metamorphoses Retold I – XVIII. The title refers to the epic poem by Ovid (The Metamorphoses, circa 1 ACE) which is a playful retelling of creation and historic myths that involve transformation. In Ratna’s Metamorphoses, parts of the body come together in a rhythmic, choreographed interplay of positive and negative spaces. Like shields/armours or cast off cicada shells they do not so much describe the figure as they allude to it. They are (literally) ‘impressions’ of the external surface the torn, flimsy, permeable membrane between the outside world and the vulnerable interior spaces. The frosty quality of the rough-hewn translucent forms suggests a Pygmalion-like birthing. As the title suggests, the forms resemble half formed pupae that have erupted prematurely from their protective cocoons, on their way to sprout wings. They seem to have condensed and formed from the very atmosphere, while also appearing to be evaporating into nothingness. This appearance of the forms being mid-process alludes to the continuous cyclical processes of making-unmaking the shattering and healing, gathering and erasure of the constructed identity of the self. Though the surface is pitted and irregular the material often manages to carry surprising, delicate details like lines of the clavicle, finger joint creases, cuts in shoulder blades, or dimples at the ankles constructing postures of a female form in casual poses at rest. The sculptures are at once as fragile and ethereal looking, as they are strong, durable and substantial.

Through time immemorial, the female form has been idolised/fetishized, revered and feared. It has been admired for its formal aesthetic aspects and cast as a passive object of the (male) gaze. The self-destructive condition symptomised by eating disorders, for instance, comes from the internalisation of this tendency to ‘objectify’ the body. The acts of purging or denying yourself of nourishment are as much an attempt to “sculpt” the body into a shape that coincides with one’s conception of an ideal.

Ratna conceived of Metamorphoses Retold with an acute consciousness of the construction of the female form as surface and image. With these self-casts, she uses her own body as a starting point in bringing up perceptions of the feminine self. By turning her own body into her work, she is, in one sense, returning to the Renaissance aesthetic that held the body as the centre of the universe, but in the same gesture she also reclaims the objectifying gaze, making the body both experience and metaphor. Opting to cast her body as opposed to sculpting it, she uses it to take an imprint treating it as a repository of content memories, stories, the residual effects of time, age, and habits. She chose to endure the difficult process of casting with strips of medical plaster and plaster of Paris which required her to hold a pose, weighed down by the weight of the material for extended periods of time (sometimes as long as two hours at a stretch) while the sculptor, Aarti applied the casting material and secured her to an armature for support. The pain involved in the rather arduous process of casting contributes to the cathartic, sublimational aspect of this process of vitalisation. While the many fragmented body-forms speak as much of vulnerability, trauma and imbalance, they may also be seen as gestures of confrontation, retaliation and affirmation. As they make tangible the artist’s very existence, in representing herself she plays with the narcissistic gaze, while deliberately splitting away from herself, looking at herself as an outsider. The ritual of casting her own body mimics the larger desire for transformation/reinvention, the multi-fragments indicate an acceptance of seeing the self as many-minded and protean. By remaking/re-presenting herself she frees herself from her own image.

This self that contains the world and expresses it, goes beyond simple confrontation with the moment. The works frame basic, universal questions: Who am I? What am I? How do I see myself? How do I look? What do you see? How do you see me? How can I be free from all these definitions? These are the question the works pose, not with the intention of framing answers, but as a way of adding to the puzzle. After all, it would be impossible to question life without first questioning ourselves.

“Even the most solid of things, and the most real, the best-loved and the well-known, are only hand-shadows on the wall. Empty space and points of light.”

From Sexing the Cherry, Jeannette Winterson.

The body-casts came from the need for a more organic involvement with her work that went beyond an object-centric approach to the process of art creation. Between the Lines preceded the sculptures cast in resin, and draws from Ratna’s formal training in Book Arts from the London College of Printing (2005). This installation, which may be seen as an experimental self portrait in abstraction, comprises a multi-tiered, wall mounted bookshelf in pine-coloured wood and acrylic, with over 25, hand-cut and -bound art books (made by the artist) interspersed with re-bound commercially available books by British writer, Jeannette Winterson. All the books have creamy-white hard back covers. The art books are small (5” x 5”), intimate spaces, containing text fragments and accidental patterning. The text that meanders in and out of the pages, like irregular murmurings against the delicate, yet vigorously treated pages of the books, comprises the artist’s introspective diary entries, seamlessly interlarded with lines of text from Winterson’s writings. The text in one of the books, for instance, reads as follows (my italics to indicate Winterson’s text):

i dont care about the facts

i care about how i feel

every moment you steal from the present

is a moment you have lost forever

trust me

i’m telling you stories

women like you to treat them with respect

ask before you touch

why do i question what i see to be real

this is the CITY OF MAZES

Sometimes the font size it so small, it is unreadable to the naked eye, suggesting a kind of the circumspect tentativeness that comes from vulnerability. Whispering at times, screaming out at others, the typographically eloquent fragments of text are not meant to be read in a conventional, linear manner but are more impressionistic recreations of the white noise buzzing in the back of a preoccupied mind. Immaculately pressed, the books are seductive and surprising, like personal puzzles that lie in wait for the unsuspecting viewer. One of them, for instance, opens with the word “ME”, the subsequent pages list a young woman’s fears, and aspirations laying herself out bare, inviting the viewer to read her like a book. Another book that starts with the word “YOU”, simply states (requests?) “Write”, followed by blank pages, inviting viewers, to be complicit with the work by ‘sharing’ themselves as she has. The abstract visuals are composed from digitally-manipulated photographs of shadows (of “Empty space and points of light…”), have been inkjet-printed on paper that is sometimes pre-textured with acrylics, some of the pages have been embroidered, some others features spare lines of miniscule text that has been deliberately defaced or obscured with paint, pen-lines or pin-prick patterning.

The books metaphorically anticipate the sculptural works insofar as pre-empting a more painterly (as opposed to a strictly design-/ function-based) approach and the act of making an imprint. The sculptures take these proclivities to a larger more involved level that engages her entire being going beyond the dependence on dexterity and skill.

Between the Lines was conceived in response to the writings of Winterson, an influence Ratna acknowledges directly in the eight black and white photographs accompanying this installation which frame parts of a female nude with the sentence, “Am I who I think I am or am I just a romantic notion in my head” ‘Written on the Body’ (pun intended), repeatedly. The relation between language, the written text and the body goes back a long way. Text has been used variously in socio-cultural practices to ornament, brand, clad and identify the body. The black and white images refer more directly to Winterson’s allusion to the body as a site. “Written on the body is a secret code only visible in certain lights: the accumulations of a lifetime gather there. In places the palimpsest is so heavily worked that the letters feel like Braille.” (Written on the Body, Jeanette Winterson.) The tactile quality of the resin sculptures seem to be a physical fruition of the meditations Between… appears to be grappling with. Winterson’s narratives constantly play with boundaries that define, restrict and determine our sense of self, gender, influence our choices, like those of fear, class, race and socio-cultural norms and expectation. The shelves and the books that are as formally straight-lined, controlled and designerly, as the lines of the sculptures are unrestrained and free-flowing, express the awkwardness of ‘boxing’ the self up in neat little labelled packages. The books play with these expectations we approach them, flipping pages by habit expecting explanatory narratives, or illustrative images, instead what we encounter are teasing invitations, elusions, suggestions and echoes that like Metamorphoses… suggest narratives that are as personal as they are universal.

The progression from one work to the next makes one impatient for Ratna’s next body of works. Will the body forms complete their cycle of self realisation and sprout their wings or evaporate altogether to scale other heights?

We wait and watch.

Madhavi Gore & Nivedita Magar

March, 2007

gallery beyond, mumbai, 2007